Pansies and Violas 1946 (approx. 9½" x 13": 24 x 33cm) Photograph: Petra van der Wal © Liss Llewellyn Fine Art. Private collection.

Still-life was never really Evelyn's genre. To my knowledge there are only six in her entire canon, and I've reproduced them all here. The genre didn't appeal to her because for Evelyn life was never still, never unproductive: life had to move, to seethe, to regenerate, to be vital and compelling. In almost the totality of her work people are present, people moving, working, playing, fulfilling her calling to express creation, and mankind's relationship with it, in all its energy and power, actual and spiritual.

What Evelyn did produce in this form owes almost everything to her mother Florence, a doughty and indefatigable painter of still-lifes, almost always floral. Pansies and Violas, above, can perhaps be taken as Evelyn's tribute to her mother, who died in 1944. It's the first of Evelyn's post-war paintings, and the first to come from Vyners, the cottage in Long Compton, Warwickshire, where she and her husband Roger Folley set up their first married home. It's as though, having put her war painting behind her, the first item on her to-paint list was an in memoriam to the mother to whom she owed so much. I don't think she painted another still-life thereafter, unless the undated 'Bramley Apples in a Colander' is an exception.

'Bramley Apples in a Colander'

nd (14 x 16in: 36 x 40cm) Photograph: Bert Janssen ©Christopher Campbell-Howes.

Private collection.

I suggest -

although I'm not convinced that it matters very much - that 'Bramley Apples

in a Colander' may come later in Evelyn's career for no better reason that

in the period 1938-47 apples appear quite often as a sub-theme in her work.

They even stray into her war painting: A 1944 Pastoral: Land Girls Pruning at East Malling is all about apples, and a Bramley, similar in tone

and texture, appears in a bowl of apples at the top of the painting. (It has to

be said, however, that Bramleys, which used to be the preferred English cooking

apple before being supplanted by European varieties, were very common indeed.)

It's likely that a study of a cineraria

in a pot comes from Evelyn's late teenage years, when she shared a tower studio

with Florence at The Cedars, the Dunbar family home in Strood, Rochester,

Kent.

'Cineraria with Letter' nd (20 x 14in: 51 x 36cm) Photograph: Bert Janssen ©Christopher Campbell-Howes. Private collection.

It's difficult to identify this particularly with Evelyn, or to distinguish it from Florence's work, other than by an un-Florentine sense of depth, some deft handling of shadow and by the inclusion of something extraneous, in this case a letter and envelope. However, the family provenance is immaculate, so no one needs doubt Evelyn's authorship.

The most surprising, indeed enigmatic, of Evelyn's still-lifes is perhaps the earliest. She's trying her hand at impasto, and certainly the roses below have a tactile quality, almost 3D feeling to them:

'Floribunda Roses' 1920 (18 x 16in: 45 x 40cm) Inscribed on verso 'Evelyn Mary Dunbar 1920 aged 14'. Photograph Michael Shaw ©Christopher Campbell-Howes. Private collection.

14! But there's just a little uneasy niggle: most floribunda roses flower in late spring and summer, so that if Evelyn is painting from the life and not from a copy, these roses must have been painted in the spring or summer of 1920, when she was 13; her 14th birthday wouldn't have fallen until December 18th, 1920. The inscription suggests that it may have been entered for an exhibition, perhaps one organised by the Rochester and West Kent Art Society, of which Florence was a member. Whether or not the inscription is strictly accurate, Floribunda Roses is an extraordinarily assured and competent piece of work and, like Cineraria with Letter above, maybe a rite of passage.

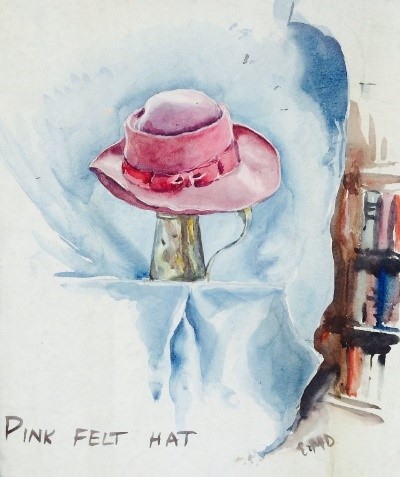

Pink Felt Hat nd Water colour on paper. Signed 'EMD' Photograph: Petra van der Wal ©Liss Llewellyn Fine Art. Private collection.

Pink Felt Hat was discovered among Evelyn's residual studio, one of the hundreds of artworks rediscovered in a Kentish oast house in 2013, having lain undisturbed since a few months after her death in 1960. I'm not aware of any context for it, nor whose hat it was to be immortalised like this, nor what fancy took Evelyn to stand it on top of a brass jug and back it with a bed-sheet. But I'm glad she did.

Finally, 'Kippers':

Finally, 'Kippers':

'Kippers' Oil on canvas nd (10 x 15in: 26 x 38cm) Photograph Bert Janssen ©Christopher Campbell-Howes. Private collection.

Nothing to say, except maybe to wish the viewer bon appetit. If you like kippers, that is.

Text ©Christopher Campbell-Howes 2017

Further reading...

EVELYN DUNBAR : A

LIFE IN PAINTING

by Christopher Campbell-Howes

is available to order online from:

by Christopher Campbell-Howes

is available to order online from:

Casemate Publishing | Amazon UK | Amazon US

448 pages, 301 illustrations. RRP £30

448 pages, 301 illustrations. RRP £30

Is the plate of kippers upside-down?

ReplyDeleteDear old friend, having disabled comments some years ago largely because someone was making a nuisance of him/herself, I was rather disturbed and ashamed to notice only today that you left several unacknowledged comments towards the end of last year. I'm very, very sorry not to have noticed this sooner.

ReplyDeleteI think the points you raise both about Evelyn's still-lifes and my essay on her perceptions of Roger Folley are entirely valid and I thank you for your input. As for whether 'Kippers' is the right way up, I reproduced it exactly as I saw it hanging on its owner's kitchen wall. The owner assured me that it was the right way up, as witness the letters MI (LK?) in the lower right-hand corner, not I think on a milk carton (surely not introduced when 'Kippers' was painted, c.1928?) but on a cloth or paper to the right of the plate of kippers. They look equally appetising either way up. If you like kippers, that is.

As for the pencil study of Roger Folley, I put myself in the position Evelyn would have to have taken in a 2-person tent in order to realise this intimate portrait of someone asleep. My supposition was to some extent confirmed by the position of the dog-tag, and to a greater extent by finding on the same sheet of cartridge paper other drawings (not reproduced in this context) with the same orientation.

But it was good of you to share your observations with me - please accept my thanks, apologies and best wishes in equal measure.